This post about cybersecurity, cyberwarfare and international law is exploring the cross sections between technology, law, and policy. Previously I analysed some strategic documents of various States (e.g. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6). So to speak: I know this landscape quite well. In 2023 the landscape is mature enough so that we can make a step further.

This will be done via a new document of the kind, which upon first sight is simply an analog document of yet another State. However, upon further analysis, you can conclude that it goes a step forward, if only due to the concreteness of examples. That is a qualitative difference. The document draws red lines and identifies thresholds of escalation in cyberspace. That is awesome because we need such clarification. So to speak: finally. The document in question is from Poland, a unique State now, as: it borders Ukraine which is involved in a full-scale war initiated by Russia. It also so happens that both Ukraine and Poland were the targets/victims of Russian cyber operations, including those with a link to the war activity. In the case of Poland, which is not at war, this was recently confirmed by Poland itself, and some cyber threat intelligence. So that’s for the tech-legal-policy-military constraints that one should be aware of at the start of 2023.

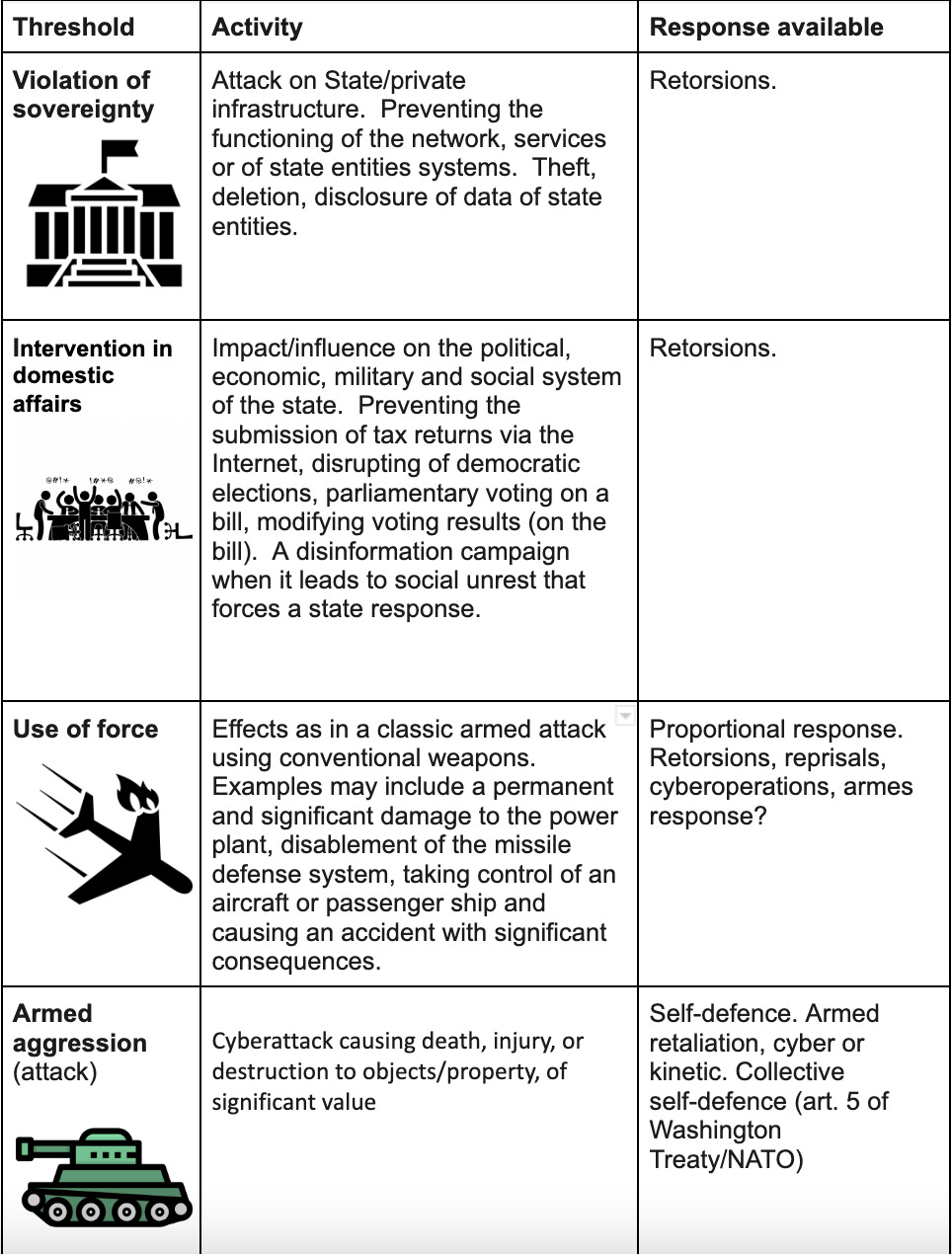

Now directly to the document. The statement acknowledges that activities in cyberspace can cross international law-defined thresholds. The cyber operation thresholds can be depicted as cyberattacks that may

- Violate sovereignty.

- Constitute unlawful interference in domestic affairs

- Constitute use of force

- Be an armed aggression.

That’s not an imaginary scale that I just made up. That’s the thing. The scale is based on international law that every State now accepts. The trick is to simply align one’s mind to conform and express in the above ways. That will make the debate healthy by becoming standardised. If you view cyber operations on the above scale, you will never again fall for the hype of “sophisticated” expressive descriptions of events that turn out to be non-events at all.

The answer to the activities on the scale 1-4 above can be diplomatic or economic retorsions, but also retaliatory (self-defence) cyberattacks (levels 3, 4). Including responses in a different domain. You know, like missiles, aerial bombardment, or artillery strikes. Here, too, the Polish Statement is bringing the important detail as it explains why this non-cyber response may be used in practice. Now, why does it matter (that I emphasise) that it is a *Polish* statement? The trick here is that it is States who have the power to shape how to understand such things. And Poland is pretty much a State (and its Statement builds on the many preceding ones: of the US, UK, Australia, and so on). Expect more clarity of the kind in future (different) State statements.

The position of the Republic of Poland defines the escalation ladder of activities in cyberspace. The scale and severity of violations and possible responses. Now, to the document.

1) Violation of sovereignty

It sounds like a pretty standard statement: “the violation of a state‘s sovereignty may occur both in the event of an attack against state infrastructure and against private infrastructure”.

It also goes further to provide examples: “… interfering with the functioning of state organs, for instance by preventing the proper functioning of ICT networks, services or systems of public entities, or by a theft, erasure or public disclosure of data belonging to such entities”.

Achieving such a threshold is pretty straightforward for a State or a non-state.

Example. Is the theft and publication of correspondence, e.g. the minister's correspondence a violation of sovereignty? Of course, it is. Regardless of whether this was the official mailbox, or the private one. This happened, probably in many places. It is only one concrete example of how State sovereignty can be violated, of course.

2) Unlawful intervention in domestic affairs

A more serious violation threshold is unlawful interference in domestic affairs. But what is this thing? To reach this level “an intervention must include the element of coercion”. While coercion is undefined, it can imaginably be direct (threat/etc) or indirect (where it is implied). That is pretty standard: “cyber operation that adversely affects the functioning and security of the political, economic, military or social system of a state, potentially leading to the state‘s conduct that would not occur otherwise, may be considered a prohibited intervention”. Those examples from the Statement are also pretty clear (the explanatory thing in parentheses is something that you will not find in other similar statements of the kind):

- cyberattack causing the prevention of the filing of online tax returns/declarations systems

- interference disrupting the reliable and timely conduct of democratic elections

- depriving the parliament working remotely of the possibility of voting online to adopt a law (please note: it is not a hypothetical risk. such a voting process is an actual technical-legal option in Poland! And blocking of the capability is easily imaginable; my point is that this is therefore not an ambiguous or general example, but a very concrete one!) or modifying the outcome of such voting

- wide-scale and targeted disinformation campaign when it results in civil unrest that requires specific responses on the part of the state [if the State need not intervene, then the disinformation is bogus, as it has no measurable effect]

About potential ways of retaliation to points raised in (1) and (2)

Typically, State practice considers that retaliation is done economically or diplomatically. Sanctions, finger-pointing, etc. That is called a retorsion.

3) Use of force

This threshold point brings us closer to military activities. Cyberattack perceived as the use of force is judged based on the effects. Which here need to have “similar” effects to those typical with traditional armed activity, with non-cyber weapons. Examples are provided: “permanent and significant damage of a power plant, a missile defence system deactivation [I’d say that this is an armed aggression level, or at least bordering on it, as it directly interferes with weapons systems of the army] or taking control over an aircraft or a passenger ship and causing an accident with significant effects may be considered the use of force”. Such activity typically involves the destruction of property/objects, causing casualties or injuries, etc.

4) Armed attack

Taking the previous point even further. Like an activity involving the destruction of property/objects, causing casualties, injuries, etc. All of it is of a significant level/value/amount. Such events could be viewed as armed aggression.

This gives the right to self-defence. A response can be in its kind so in this case a cyberattack. It can also be via any other available (i.e. non-cyber, too) means. The explanation is as follows: “Deprivation of the right to respond to such a cyberattack with kinetic means could render the self-defence right illusory when the perpetrator of an armed attack is little dependent on its functioning in cyberspace”.

So one imaginable option to use non-cyber force is when the perpetrator/target in question is not relying on ICT too much. Indeed, in such a case, the imposed costs on the adversary could potentially be too low to bother. Hence, this is why States include the option to use aerial bombardment, artillery, etc. However, such a scenario has some limits.

Imagine that Poland (Germany, Norway, etc.) is cyberattacked by a remote State. Let’s say, one based in South America. In what way a non-cyber response could be employed? Poland (Germany, Norway…) is quite far from South America. To use a missile/bomb/aerial with a proper range would be impossible. That’s one limitation of such word-rattling about the potential of “whatnot responses”. Because sometimes it is simply just impossible in practice. Another scenario. For years, Russia has been working on disconnection capability from the global internet. Would that be an argument for a non-cyber response? Not quite - Russia would still rely on ICT, just domestically in its isolated networks. And connecting to their isolated networks might not be so difficult in the end. So that, too, would not be a crucial ground to trigger such a response (which is actually stabilising, in our world…?)

Other comments.

Obligatory comment. Poland says that a State may take action also against non-state actors. So private firms, individuals, “hacker groups”, etc. That’s interesting, though it should not be surprising to us by now. Many States likely feel the same way (so let them speak up?). If a hosting State refuses to take action against the exploitation of its territory, then it is not meeting its due diligence obligations.

About laws of armed conflict – sadly, Poland only devotes 4 sentences to the fact that international humanitarian law applies to cyberwarfare. So nothing is explained here.

Unfortunately, also, the position contains an internally contradictory statement. The statement says that cyberspace has somewhat of a "non-territorial" character. But in a different place it correctly (!) states that the principle of sovereignty, which is related to territoriality, applies. The two cannot be true at the same time and in the same document. That would defy logic. In the context of cyberspace, sovereignty includes, for example, digital infrastructure, and therefore the aforementioned “non-territorial” is not the case.

All in all, over the previous 10 years we’ve seen a dramatic clarification of how “the rules” apply to “cyberattacks”. It is more and more untenable to speak of “grey zones”. Good.

Find the escalation ladder below.

Did you like the assessment and analysis? Any questions, comments, complaints, or offers of engagement ? Feel free to reach out: me@lukaszolejnik.com