In my book I gently touch upon a problem often framed as a technical story about algorithms and content feeds. The “information bubble” or "echo chamber" model suggests that most people are locked into agreeable content, which locks them from changing opinions and induces group animosity. Yet the preference for agreeable content and agreeable connections exists offline as well. The claim that online environments systematically trap most users in tight ideological spaces is harder to defend without careful measurement and it's mostly postulated by a proof of anecdote, a string of publicist takes, and a few works trying to demonstrate it by validating data from social media. The strongest version of the filter-bubble hypothesis often conflates two claims: individual-level personalisation and society-wide polarisation. The jump from the first to the second is not really supported.

A second layer is psychological and social. Contact with opposing views can feel unpleasant and can trigger defensive reactions, so exposure alone does not reliably move people toward the middle. The strongest bubble model also assumes a paradoxical user who actively selects information yet becomes largely passive once algorithms organise exposure.

A useful correction is to look beyond content channels and ask what changed in the structure of everyday relationships. The most visible shift of the last two decades is indeed the spread of digital platforms and smartphones that make communication easy, cheap, fast, and constant. One result is that people can sustain more ties than before, with significantly more people than in previous ages. That matters because close ties are the people who exert the most significant (i.e. even everyday) influence. Not only the content of other people that appear in a feed.

U.S. trends link the post-2000s rise in polarisation with a rise in close social connectivity. Polarisation measure built from consistent survey items rises sharply after the late 2000s, from around 0.11 prior to 2010 to about 0.19 in 2017. Across multiple countries and surveys, the estimated average number of close friends doubled over time, moving from about 2.2 in 2004 to about 4.1 in 2024. It clearly goes up since around 2009. The proposed mechanism could be quite simple. People tend to prefer those who think similarly, and they often adjust views to reduce local tension in their immediate network. This can be described as seeking agreement with friends and, when relations turn hostile, moving toward disagreement with enemies. Once the density of positive close ties crosses a certain threshold, a rapid shift toward fewer, larger, more opposed groups ensues. Such an elegant model.

This perspective narrows what the strongest version of the “bubble” story can explain. Browsing data from 2013 comparing different routes to online news shows modest differences in ideological segregation across access types. Most consumption comes from habitual direct visits to familiar outlets (i.e. expressing the familiar takes or adopting familiar stance), and cross-side reading stays low. Also, perhaps surprisingly to some, politics is only a narrow part of most people’s everyday social life.

The main driver may not be a universal system of "echo chambers" that seals people inside content bubbles. It's much simpler to observe that people like the familiar and what appeals to their existing emotions and opinions, tied with the increased number of close ties, which all increases up the feedback cycle around identity and politics. Because new close ties are usually easier to form with people who already seem similar or subscribe to similar views, rising connectivity can sort networks into more uniform clusters. When opposing views appear inside this denser social world, the encounter can harden existing beliefs rather than soften them.

On this reading, “bubbles” look more like an effect of social reorganization in a high-connectivity environment than a primary cause. Therefore focusing on symplistic reasons for the rise of discontent or proneness to disinformation is too simplified and must lead to analytical errors and bad diagnoses, including for tackling information operations, disinformation and propaganda.

The strong version of the filter bubble hypothesis, that algorithmic personalization traps individuals in isolated information chambers, is not supported by evidence. People continue to encounter diverse viewpoints, particularly through social media, and most news consumption still follows traditional patterns of directly visiting sites.

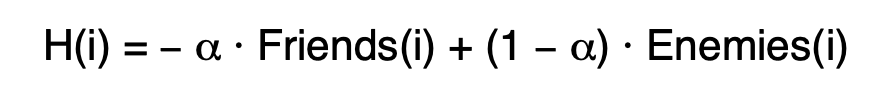

Friend-foe model describing the relative "stress"

The mechanism can be captured in a neat formula. Let's define a simple model of cognitive dissonance minimisation where each person strives to reduce local worldview tension within their immediate social environment. Let's consider this local tension as H(i). Let's assume that, in a social network, such a person has two categories of ties: Friends and Enemies, understood as people with relatively aligned or relatively opposed views. The model assumes two parallel goals: greater agreement with friends, and greater disagreement with enemies. This is not a description of moral intentions, but a simplified representation of a mechanism that reduces “discomfort”.

In this reading, Friends(i) denotes the total level of alignment between person i and their friends, while Enemies(i) denotes the total level of alignment between person i and their enemies. Agreement with friends lowers tension. Agreement with enemies raises it. When a person changes a particular opinion, a positive change is one that brings them closer to friends and further away from enemies, in terms of alignment.

The parameter α specifies how strongly agreement with friends matters relative to disagreement with enemies. If α is equal to or greater than 0.5, the model places greater weight on maintaining cohesion among friends than on deepening differences with enemies. This matches the intuition that stability within one’s immediate circle matters more than actively intensifying conflict beyond it. In that sense, informational and propagandistic operations involve assessing and accounting for these realities and/or shaping them.

- H(i) < 0 - more agreement with friends than with enemies, lower tension.

- H(i) > 0 - too little agreement with friends and/or too much agreement with enemies, higher tension.

This leads to the conclusion that “agreement with enemies” - for instance accepting their arguments - can be costly for people. It creates an incentive to maintain differences and disagreement. In this dynamic, even careful analysis and fact-based arguments can be perceived as a threat to the cohesion of a given social group.

I am open to new engagements. Feel free to reach out me@lukaszolejnik.com.